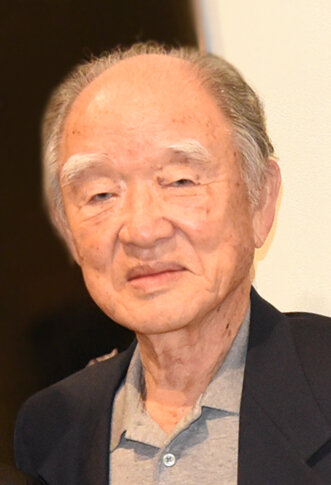

Junji Sarashina:

Shining a Light on Horrors of Atomic Bombing

By GWEN MURANAKA

Junji Sarashina with his family: Melissa, Kiyoko, Stephanie, Junji, Emily, and James

“I’m still alive. If I don’t speak up, who else is going to speak up?”

Ninety-year-old Junji Sarashina has made it his mission to share the horrors he experienced as a young teen on a sunny morning in August 1945.

But the contours of his life do not just run through Hiroshima, Japan. He is a father, a grandfather, a community leaders and, it turns out, a great volleyball player.

Junji speaks with the soft lilt of pidgin, reflecting his childhood growing up in Hawaii as the youngest of five children. His father Rev. Shinri Sarashina was the head minister of Lahaina Hongwanji Mission on the island of Maui. His mother, Toshiko, taught Sunday school and instructed young brides, who lived with the family, on domestic matters such as cooking, sewing and even music.

“She was very, very popular — more popular than Dad,” Junji said with a laugh. “When I was young I was thinking, ‘Gee, how come I have so many sisters?’ I had a nice life, small town, everybody knows each other.”

The Lahaina church was a gathering place for the community where they would show old movies in the basement. Children of plantation workers played together. Junji recalled seeing whales breaching in the distance, thinking they were giant fish.

“It was a pleasant place because all the Japanese kids, 200 or 300, came to church after English school because parents worked in the sugar plantation and pineapple factory. Ladies made musubi. Kids said ‘I don’t want to go to Japanese school but I want to eat the musubi and takuan.’”

In 1937, the family moved to Honolulu where Junji spent a year when his father became Fuku Rinban of Hompa Honwangi Missions of Hawaii. “It was a big change moving to Honolulu. You were no longer in charge of the members of Lahaina. But ministers are always moving.”

After just one year on Oahu, his oldest brother Kanji moved back to Japan to prepare to take over the family’s temple in the future. His parents decided that the entire family, except for his father, would return with him. Their destination: the Nakajima District of Hiroshima.

Hiroshima, Japan

Today, Nakajima is the location of the Hiroshima Peace Park. In 1937, Nakajima was a busy downtown district, located in the delta between the Motoyasu and Hon rivers.

Junji entered the second grade and initially had a hard time speaking Japanese but found he could make friends easily. “They didn’t tease me,” he said. “I made friends.”

School in Hiroshima was a contrast from Hawaii. Every classroom had a photo of Emperor Hirohito, and students would bow to the photo. Eventually there were tell-tale signs of Japan’s military expansionism, as the island nation went to war with China. By 1940, Japan would join the Axis Powers of Germany and Italy. He vividly remembered seeing young men being sent to war.

“When they leave the town, they were forced to say farewell to young soldiers, so that young man going out to war see 200-300 people saying, ‘Banzai! Banzai!’

“Later on we started to see the Army sergeant was always there, trying to teach us how to become soldier, how to obey, how to conduct yourself, for future soldiers for the military.”

As Junji begins to describe the most harrowing day of his life – August 6, 1945 – he says: “This is hell.”

The day didn’t start that way. Junji was 16 years old, working at a munitions factory in Minamikanon-machi, where they made anti-aircraft explosives. Even as civilians toiled to produce weapons of war, there was a sense that the tide had turned against Japan.

“You could tell Japan was losing the war,” Junji said. “Same time see B29 fly overhead, that’s common sense, deep in here you know it.”

At 8:15 a.m., he stepped out of the factory building. Overhead, the Enola Gay B-29 bomber had just dropped the atomic bomb over the city. Junji was just two miles from the hypocenter. When the bomb exploded, Junji’s world became orange. “I felt a tremendous orange glow, the whole world was covered with orange glow. “To me it was nothing but orange glow all around me, at the same time, the force and explosion was so strong that it knocked me flat on my face. And the explosion was phew! One way and phew! The other way because of the vacuum.”

Because he was standing next to a concrete wall, he escaped the brunt of the blast. “If I was two steps late, I would have been exposed to the orange ray with radiation,” he said. “If I was five steps ahead of me, I would have been next to window glass that would have hit me, a thousand pieces.

“I just happened to be in right spot and right time.”

Junji and his friends were able to leave the factory and walk to one of the bridges going into the city. At the same time, people were crossing the bridge, trying to escape. “Some were burned, their skin hanging, bleeding all over. And we’re trying to enter and they’re trying to come out, we realized it was impossible to go in,” he said.

“One of the reasons I might be still alive is because I didn’t go to the city right away. That night, the whole city, from one end to the other, was burning. At times you could still see flames shooting up to 40, 50 yards high due to thermal columns. Some of school friends were crying because their parents, their homes, sisters and brothers were in that burning city.”

The following morning on August 7, Junji and his friends went back into the city looking for friends at the dormitory. The bridge that they had tried to cross the day before was covered with bodies. “The wounded were piled upon the street and bridges. Almost had to step on people to go across the bridge,” he said.

On the way, they stopped at a Red Cross station, just one mile from the hypocenter. He recognized classmates among the injured and dying. “I saw five young students from school burned and wounded laying on the floor. What can I do for them? No medication, no bandages. So I said I’ll give them a blanket. Rolled a dead person off blanket and gave to the five kids.

“They said ‘mizu chodai (water please).’ We were told not to give water to burned persons, but I thought, they’re not going to make it, so why not give them some water? “I walked around found a can, somehow got some water, gave water to the young boys, one sip at a time. Some couldn’t even swallow. Sure enough a little while later they didn’t move. I have no regret giving them some water. That was their last wishes. One of them said “arigato.’”

At the dormitory, Junji helped to collect lumber to cremate the dead. It would be two days before Junji arrived back at the temple where his mother worriedly waited for him.

“When I reached home, my mom flew out of the house and hugged me and she was crying. She hugged me so hard that I couldn’t breathe. She told me, ‘I’m sorry Jun-chan, I couldn’t go into town to save you and I told her ‘Mom, I’m glad you didn’t come into the town. It was terrible.’

“Until that time, under such tragedy and catastrophe I had lost the sense of ordinary human beings,” he said. “Maybe I was moving around survival with a survival instinct only. Mom’s hug brought me back to normal human being at that time.”

Postwar Return to America

The war had a profound impact on the entire Sarashina family, separating them for its duration. Junji’s father was arrested immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941 and spent the rest of the war falsely imprisoned in internment camps in the mainland.

Both of his older brothers were drafted by the Japanese military. Bob served in the Japanese Navy. Tommy was drafted into the Army and went to China and Manchuria as an infantryman. Captured by Russians, he spent two years as a prisoner of war in Siberia. That terrible time would continue to echo through Junji’s life, but it would not completely define him. After the war, Junji went back to Lahaina and then to Honolulu where he worked an announcer at a Japanese radio station.

Drafted by the U.S. Army during the Korean War, he used his Japanese skills serving in the Military Intelligence Service and he remained in the Army for six years. He worked as a driver for a general in Korea, among other duties. “I was lucky, I didn’t go to the front lines,” he said.

In another instance he fondly remembered when he was invited to play volleyball with the Green Berets while stationed in North Carolina. Junji had played the sport during high school and college, and his abilities became apparent in matches with other Army units. “We kept winning and winning, so finally the Green Berets asked me to join their group for the All Army volleyball tournament.

“I was the smallest one in the group. The regular guys were all tall. I played a Japanese style volleyball. The coaching is totally different, how to distribute the ball was very unique.”

After Junji left the Army, he moved to Orange County where he worked as an engineer for Northrop Corporation.

In 1956 he married Kiyoko, who is from Hiroshima. They had two sons, Richard and James. The family became active in the Orange County Japanese American community. Junji and Kiyoko are members of Orange County Buddhist Church. Junji served as president of the Buddhist Church and Kiyoko was president of the women’s association.

During the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, the Sarashinas helped out the Japanese wrestling team. Several team members couldn’t properly digest American breakfasts – cereal and milk in particular – so Kiyoko and other OCBC women made them miso shiru and other Japanese fare. They delivered the meals to the Anaheim Convention Center, where the wrestlers were training.

The athletes showed their gratitude with an unforgettable gesture of appreciation. “The medalists put medal around my wife’s neck, 5 medals: gold, silver and bronze,” Junji recalled.

For decades, Junji has been a leader of hibakusha — survivors of the atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As president of the American Society of Hiroshima-Nagasaki A-Bomb Survivors, he has shared his story and also helped to coordinate medical checkups with doctors from Hiroshima. Doctors travel from Hiroshima to carry out medical exams of survivors throughout the United States. The horrors of radiation, unknown at the time, continue to manifest decades later.

Today there are fewer than 200 survivors who are members of ASA and the number gets smaller every year.

For the first time, the story of Japanese American atomic bombing survivors is being told in an exhibition currently on display at the Japanese American National Museum. “Under a Mushroom Cloud” features the damaged possessions left by the victims. Hiroshima and Nagasaki collected and preserved these artifacts, including clothing and other personal items. The exhibition is a culmination of Junji’s efforts to inform the public about the horrors that he experienced.

As part of the opening of the exhibition, which coincides with the 75th anniversary of the attacks, Junji spoke about his experiences, alongside fellow hibakusha Howard Kakita. He said he hoped the exhibit would draw media coverage and help better inform the public about the horrific events. Several organizations, he said, have expressed a desire to bring younger generations to the museum.

“I have done this for over 60 years, but isolated small things,” he said of his lifelong mission to share his story and aid hibakusha. “I’m so thankful that a big organization like museum is sponsoring this exhibition.”